Walking on Eggshells, What's Going on Inside of People

The fear of the "bomb" going off is a common fear

Human interactions that present walking on eggshell exchanges are stressful territory to traverse. There is a lot happening emotionally and psychologically in each person’s mind. A public figure recently talked about it, inspiring the following conversation.

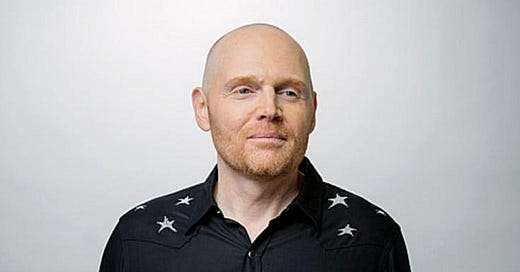

Comedian Bill Burr knows he has an explosive temper. He’s not a cold anger person. It’s out in the open. In a stand-up routine he mentioned how his predictable nature with upset has put his wife in a place to where she, according to Burr, apprehensively approaches certain requests with him.

He continued with an example in which his wife was “really timid, like she was trying to figure out which wire to snip so the bomb doesn’t go off,” Burr said about his anger, while pointing at himself.

At the end of his joke, he makes a gesture of his wife having to snip the wire as she hesitantly finishes making her request.

People who act as Burr says he does may be blind to what is going on within their mind and why they put other people in highly uncomfortable or fearful situations.

“Most likely, except in extreme cases — abuse for example — we are unaware that we are creating this dynamic,” says Dana Marcus, LCW, is a therapist and and founder at Dana Marcus Psychotherapy. “Folks who cause those around them to have to walk on eggshells are generally emotionally immature and lack both emotional intelligence and insight.”

Creating this dangerous emotional and psychological landscape could be purposeful.

“Those who are narcissistically oriented derive satisfaction or psychological 'supply' when they cause those around them to calibrate to them constantly,” Marcus says.

People who are so reactively intense to the point where others are uncertain, uneasy or afraid around them, “often have a difficult time self- regulating their emotions and are easily activated by other people, places and things,” says Shari B. Kaplan, LCSW, a trauma-informed therapist, speaker and founder of Cannectd Wellness and The Can’t Tell Foundation.

“People who are easily activated often have unresolved chronic or traumatic stress, early childhood drama, neurological and mental health challenges, chronic pain or illnesses or unresolved pain or grief.”

It can be difficult for them to know why they are acting in an extreme manner.

Such a person “is struggling emotionally and psychologically in ways they might not fully recognize,” says Allison Chase, PhD, the senior clinical advisor at Eating Recovery Center and Pathlight Mood & Anxiety Center.

“Often, there's a heightened sensitivity to feeling judged, criticized or rejected, causing them to react defensively or intensely, even when that wasn't the intention.”

Deep inside, there can be significant turbulence that isn’t clear to other people

“They might be managing deep insecurities, unresolved emotional pain, fears about not being good enough or losing control,” Chase adds. “This kind of intensity tends to push others away or create tension in relationships, which is exactly the opposite of what the person likely wants or needs.”

This means, the way to healing and improvement has a specific path.

“Recognizing what's happening inside is the first step toward addressing these issues, creating a more comfortable space for genuine and meaningful interactions,” Chase says.

It Impacts and Conditions the People Who Experience It

“When someone regularly feels they have to 'walk on eggshells,' it creates a sense of ongoing anxiety and emotional tension,” Chase says.

“Over time, emotionally and psychologically, it leads to increased stress, self-doubt and diminished self-esteem, as they constantly second-guess themselves or hold back from expressing their true feelings and needs.”

This naturally leads to changes in responses, out of perceived necessity.

“Behaviorally, people become overly cautious, avoidant of conflict and hesitant in their interactions,” Chase points out. “The real issue with becoming conditioned this way is that it limits authenticity, creates barriers to healthy communication and can prevent individuals from advocating for themselves or setting important boundaries.

“Ultimately, this kind of conditioning can undermine their emotional well-being and negatively impact their relationships and sense of self.”

It’s unsurprising that people proceeding cautiously or fearfully do so because of the instinctual part of their brain.

“When one feels compelled to walk on eggshells they typically feel under some type of threat. The threat can be conscious or unconscious,” Marcus says.

“An example of a conscious threat is when one parent is forced to interact with another, narcissistic or abusive parent, after a divorce. The conscious threat could be derived from the fear of not having financial needs met, or related to custody or time spent with children.

“An example of an unconscious threat is when someone walks on eggshells because they fear abandonment. Perhaps they had a parent who died and now walk on eggshells with their partner as a way to people please, out of fear of angering the partner and possibly losing them.”

She details what is problematic about becoming conditioned by painful experiences.

“Over time, it erodes our sense of self. When we become habituated to always put others needs above our own (such as), ‘I need you to stay calm so I will walk on eggshells to achieve this,’ resentment builds because our needs go ignored.

“Constantly ignoring our own needs causes us to lose track of what they are, breeding codependency and robbing one of their autonomy.”

“For the family members, friends, or coworkers who work with these easily-activated individuals, life can become unpleasant and challenging,” Kaplan explains.

“If you’re an adult and live in this environment, you might find yourself in frequent arguments or you cater to the volatile person by people pleasing and and even lying to the volatile individual.

“The lying occurs as a way to decrease the activation that could possibly happen for the individual. This works out sometimes but often if the volatile person discovers the lie, it will often make the situation much worse.”

It changes how children process and respond to people and stressful interactions.

“Being with an easily-activated individual, can cause a child to live in a hyper-vigilant mode because they have to look out for their own safety,” Kaplan says.

“Often times, this is not conscious, it is the adaptation response to being in an unsafe situation, whether it’s unsafe, emotionally or physically. The child often learns quickly that they cannot get their basic needs met unless the parent or adult in the household is happy or calm.

“They may learn how to people please in order to keep the adult calm and create an environment where they can get their food clothing, shelter and safety needs met.

“The child will either behave in a way that caters to the volatile individual with people pleasing or they will act out against the adult. The child that will instigate the activation, does so, as a way of controlling their own anxiety as to when the activation of the volatile individual, the rage or meltdown will occur.”

Coping

“As painful as a coping tool that this seems, both people pleasing and instigating activation are ways for the child to feel a sense of power in a powerless situation,” Kaplan explains.

“The child may also develop negative beliefs about themselves that are repressed such as I’m bad, I’m a burden, I’m powerless, I’m not safe and I’m not good enough. This is one of the ways the cycle of violence or generational trauma is created.”

People can take steps to learn how to not put people in anxious, dangerous situations with their displeasure, anger or rage.

“Learning how to regulate our emotions is critical,” Marcus stresses. “If we can tolerate our own distress, we are less likely to cause those around us to walk on eggshells as a management strategy.

“Additionally, understanding why we're so angry in the first place can help us to dissolve this dynamic, resulting in healthier interpersonal dynamics.”

There are smarter, more effective ways to communicate and problem solve.

“I suggest they try responding with clear, calm communication, focusing on expressing their feelings and using ‘I’ statements, with some validation,” Chase recommends.

“It can be helpful to focus on expressing their feelings and needs rather than worrying about managing the other person's reactions,” she adds.

Kaplan offers suggestions for those suffering harm

“Encourage the volatile person to seek help to develop their own self-regulation tools and get some insight into help how they can better manage their activation buttons. Only do this if the volatile person is safe enough to have this conversation with.

“Learn de-escalation tools and techniques. Learn things to say and do that can keep you and others emotionally or physically safe when someone starts to become activated.

“You’re not lying to a volatile person if you’re learning how to speak in a compassionate language that maintains healthy boundaries and also takes into consideration the limitations of the volatile person.

“Honesty without compassion is cruelty. People who are easily activated are also in pain and need help,” Kaplan says.

Takeaway Support Point

“It’s important that you know the difference between walking on eggshells and a dangerous situation that you need to get help for and, or possibly get away from,” Kaplan says. “They are caring professionals who can help. You are not alone.”

This newsletter normally publishes Tuesday, Thursday and Sunday, with occasional articles on other days. To advertise, link to your business, sponsor an article or section of the newsletter or discuss your affiliate marketing program, contact CI.