Disappointment and Frustration: Being Pigeon-Holed in Your Work

How it can happen and what can be done about it

Being skillful and profitable as a professional is satisfying yet maybe, not always fully.

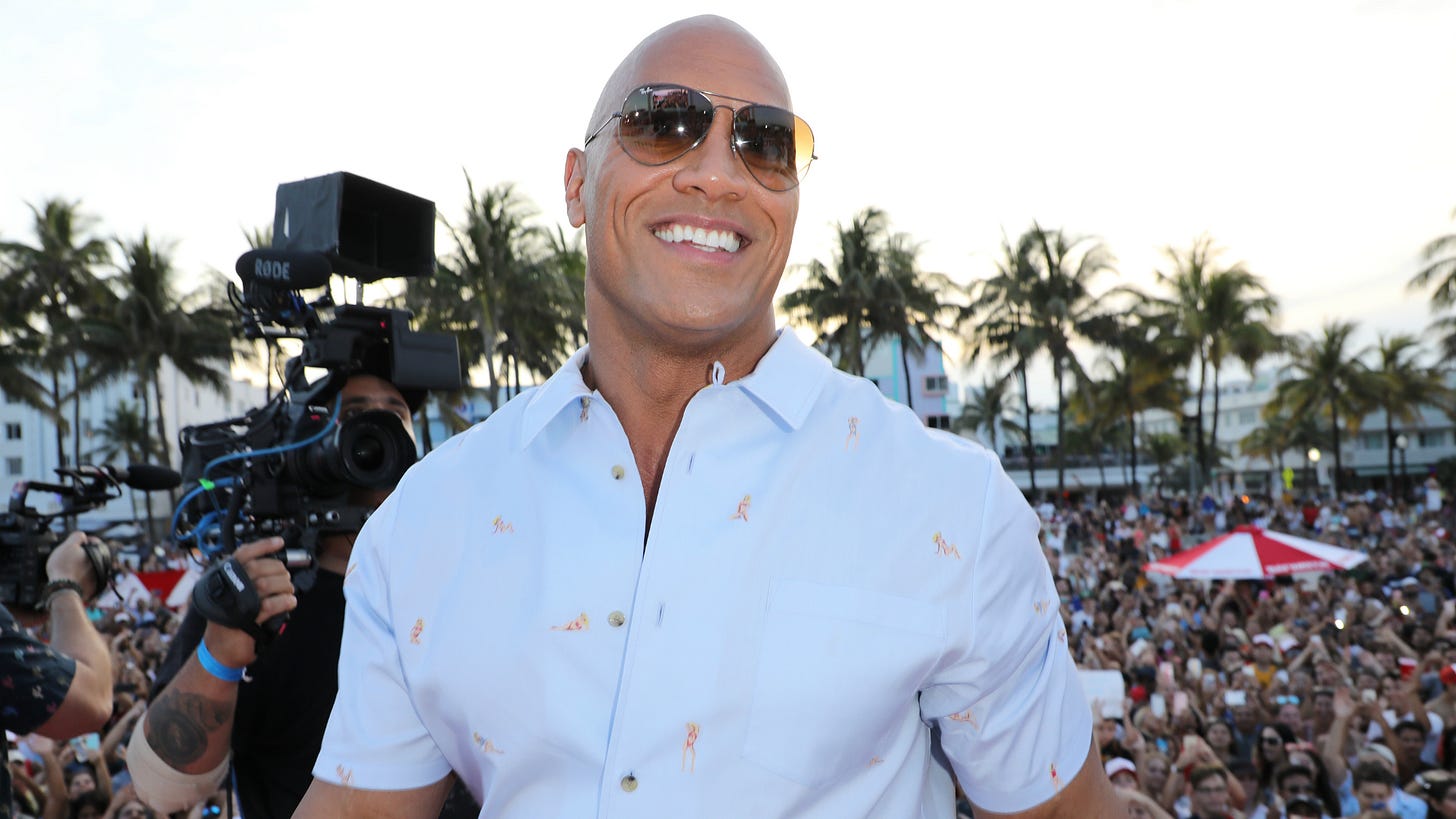

Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson talked about, for all his success, fame and fortune, that he has struggled with being limited in opportunities to do different work outside the norm in his career.

Readers may be able to empathize because of their own experiences.

“A lot of times, it’s harder for us, or at least for me, sometimes to know what you’re capable of when you’ve been pigeon-holed into something,” he told reporters in Venice, Italy at the 82nd Venice Film Festival.

He detailed how it has gone for him.

“This is your lane. This is what you do, and this is what people want you to be, and this is what Hollywood wants you to be,” Johnson said. “And I understood that. And I made those movies and I liked them and they were fun. Some were really good and did well and some, not so good,” Johnson said.

“You know, when you’re in Hollywood, as we all know, it had become about box office. And it can be very resounding and it can push you into a category and into a corner,” he continued, before admitting that he submitted to that commercial pressure.

Yes, Johnson has enjoyed his success and yet, he also has felt held back and denied from testing his skills and potential to do different types of meaningful work.

He was considered too valuable at what he already excelled at in his industry for decision makers to invite or allow him to do more and possibly succeed at that as well.

This happens to people in different fields, which is a point worth examining, which this two-question discussion does with four professionals: from the fields of communications, technology, medicine and addiction, and surgery.

The insights given may speak to readers, regardless of the type of work that they do.

“It happens all the time,” says Christa Haberstock, a keynote speaker, author of Become a Bookable Speaker and founder and president at the See Agency, a speaker management firm.

“People get recognized for one thing they do really well and that becomes their lane. Employers, industries and audiences tend to keep them in that box. It is comfortable for everyone else but frustrating for the person who knows they can do more.”

She briefly delves into the science to further explain what is happening.

“Some of the research explains it through the Johari Window,” Haberstock says.

“There are four panes of self-awareness. The third pane is what you know about yourself but others cannot see. That hidden area is where untapped skills, ambitions and passions live.

“When you are pigeon-holed, the world only sees what fits in the open pane and the rest stays out of sight. That is why talented people feel blocked. It is not that the skills are missing, it is that they are invisible to others.”

Opportunities aren’t often made available yet there are ways to think about retaining star performers while encouraging them to pursue what excites them more.

“We see this constantly in tech,” says Oleksii Kratko, founder and CEO at Snov.io, which helps customers find leads, automate cold outreach and close deals.

“It’s the rule, not the exception.”

Kratko paints a picture to illustrate.

“A brilliant support agent is deemed too valuable to move into sales engineering. A top-performing salesperson is discouraged from product management,” he begins.

“At our company, we actively fight this by creating internal internship programs, allowing team members to spend 10% of their time on passion projects outside their core duties.”

He reveals how that has aided the company which doesn’t want to lose skilled specialists who are producing at a high level.

“This has uncovered hidden talents and prevented the stagnation that Johnson describes,” Kratko says. “The greatest barrier to growth isn’t a lack of capability, but an organization’s reluctance to redeploy proven success.”

“In healthcare, this phenomenon is epidemic,” says Chad Elkin, MD, a board-certified addiction medicine physician and the founder and medical director at National Addiction Specialists.

“I see brilliant addiction specialists who want to move into healthcare administration or policy work but get trapped because hospitals need their clinical expertise.”

What seems protective of organizational interests has unforeseen costs: causing different types of stress in the high performers that that deeply value.

“The medical field especially suffers from this,” Elkin says. “We’re told to ‘stay in our lane’ of patient care. When I transitioned from traditional practice to founding a telehealth company, several medical groups tried to retain me by offering higher clinical compensation rather than supporting my entrepreneurial vision.”

It made sense to those benefiting from Elkins’ expertise and success.

“They valued my patient outcomes too much to let me explore business innovation,” he remembers. “I had to leave entirely to prove telemedicine could work for addiction treatment.”

“This happens constantly in medicine, where specialization can become a prison,” says Jose Soler-Baillo, MD and MS, a board-certified plastic surgeon.

“Early in my career, colleagues questioned why I was developing stem-cell improved procedures when traditional methods were ‘working fine.’

“The medical establishment often rewards staying in your lane because it’s predictable and profitable for institutions.”

What he has observed has pained him.

“I’ve seen brilliant surgeons stuck doing the same procedures for decades because hospitals and patients expect them to be ‘the breast guy’ or ‘the nose guy,’” Soler-Baillo says. “The moment you try to expand, you face skepticism about your competence in new areas, even when your foundational skills are identical.”

One might falsely conclude that most successful people at the top of their profession have negotiating power to do more work that appeals to them.

As the sources in this article have communicated and as someone like Johnson learned too, the best at what they do can feel or be blocked from expanding their skill set and experience.

If a highly-visible professional like Johnson or anyone excellent in their field can feel a low ceiling imposed on them, it may be worse for those less seen or well known.

“For people without celebrity status, the barriers are exponentially higher because you don’t have leverage to demand different opportunities,” says Soler-Baillo.

“When I developed ‘The Angle’ technique for jawline improvement, I had to perform it successfully dozens of times before anyone would even discuss it at medical conferences.

“Most professionals don’t have the luxury of a platform to showcase their expanded capabilities. They’re trapped by their resume’s narrative and can’t get the chance to prove they can do more, creating a vicious cycle where lack of opportunity prevents skill demonstration.”

Being lower profile in the eyes of others can feed the pigeon-holing thinking.

“The less visible you are, the easier it is for your hidden strengths to stay hidden,” Haberstock says. “The world only sees what you are known for, not what you are capable of.”

That’s become part of her work.

“This is why I speak and write about The Obvious Advantage,” Haberstock says. “Everyone has it but most people are blind to it. It is the thing you do so naturally you almost dismiss it, while it is the very thing that sets you apart. The challenge is bringing that to the surface so others can see it too.

“Once you move those hidden strengths into the open, you stop being pigeon-holed and start being valued for the full scope of what you bring,” she contends.

Traditional thinking suppresses potential and competence.

“The invisible healthcare workers face crushing limitations,” Elkin says. “I’ve worked with nurse practitioners who understand addiction treatment better than many physicians, but they’re never invited to legislative hearings or policy discussions.

“Their frontline expertise gets dismissed because they don’t have the ‘right’ credentials.”

Elkin has led a response to counter this pigeon-holing.

“We’ve promoted several counselors into program development roles specifically because traditional healthcare hierarchies would never recognize their innovation potential,” he says. “One of our best treatment coordinators now designs our patient engagement protocols, something no hospital would have allowed her to attempt.”

“The lack of a public platform makes it infinitely harder,” Kratko says. “For someone without The Rock’s fame, the pivot isn’t negotiated on a global stage, it’s built in the quiet hours through self-education and side projects. The challenge is greater but the strategy is the same.”

He tells of his personal experience.

“My transition from teaching to tech… I coded at night and sold software on the side until my new reality overshadowed my old label,” Kratko says. “Build a small, tangible proof of concept for your ‘what if?’ that is so compelling it shatters the pigeonhole you’re in. Your new capabilities, demonstrated concretely, become your voice.”