Desperate to Be Trusted Again

To be released from judgment and feel a sense of belonging and safety is a strong need

People can position themselves, unintentionally or intentionally, where they become far less trusted or distrusted.

For most, that is an uncomfortable or deeply painful reality.

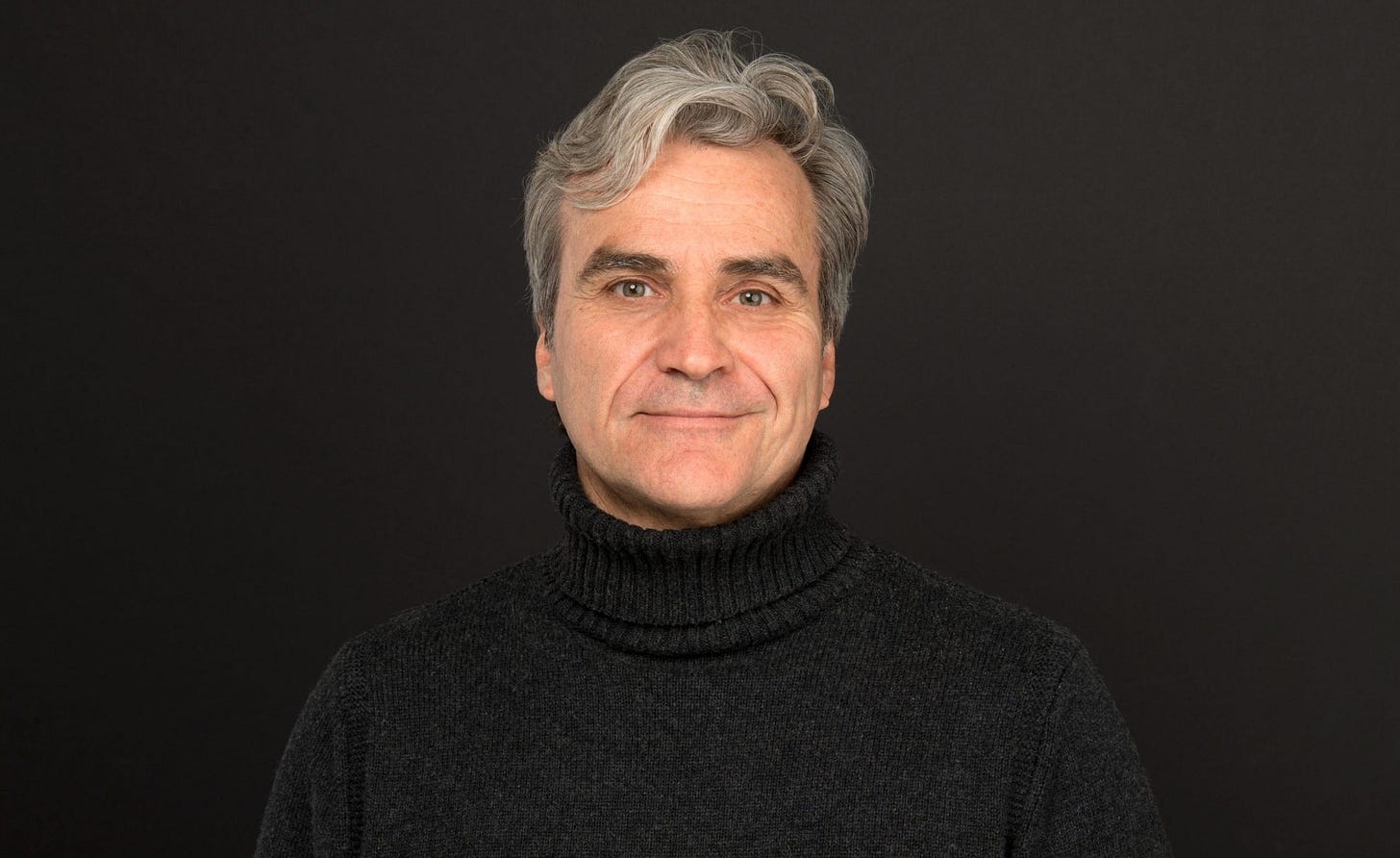

Tom Junod recklessly worked himself into that hurting spot after he wrote an article that was published about actor Kevin Spacey.

"That story had the reek of bad faith to it, to be quite honest with you," Junod admitted when interviewed by Atlanta Magazine in 2019, noting that the negative response to his profile had stalled his career.

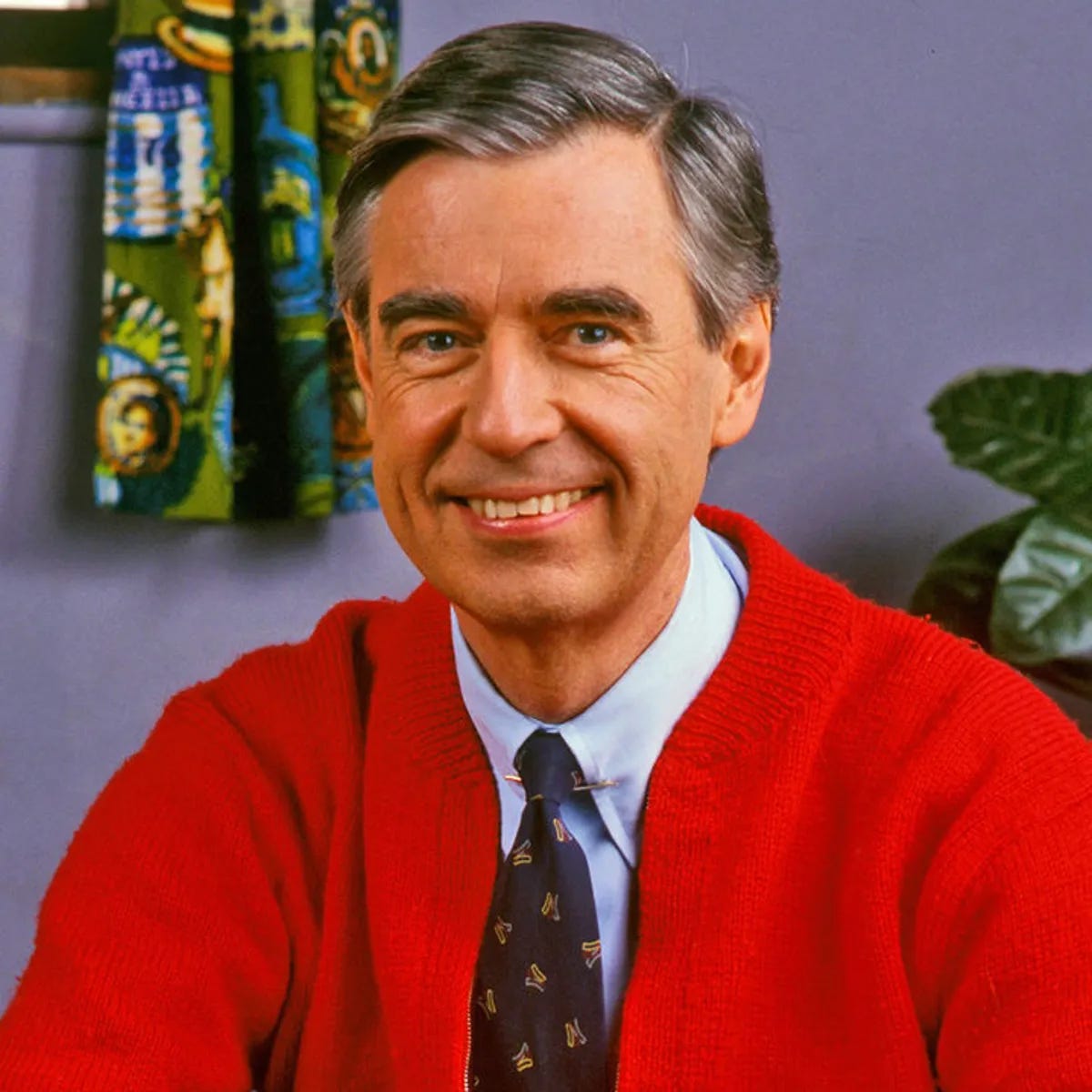

Junod, a long-time magazine writer and author, explained in a Substack interview that when he first met Fred Rogers, of Mister Rogers fame, to interview him for a 1998 Esquire profile that became widely read, he was given an emotionally-moving, surprising gift of care.

“He trusted me, which is what I was desperate for at the time,” he said.

“I didn’t even know it but I was desperate to be trusted.”

At the time, Junod didn’t know if he would again be viewed positively in his work with subjects that he would be interviewing.

Rogers, he wrote of in 2019, “trusted me when I thought I was untrustworthy.”

Something powerfully restoring took place after Junod had been deemed professional unsavory by Spacey and critics.

When someone errs, especially when badly, in judgment and is viewed in a negative light and criticized, it can be hurtful, depressing and a heavy burden.

Yet someone may feel deep, sincere remorse and want to make things “right” without knowing how. The consistent feedback that they are getting from others may be harsh, as may be their internal dialogue (self talk).

This can be a significant, damaging hit emotionally and psychologically.

“This state of limbo, where one feels remorse but cannot find a pathway to redemption, triggers a shift from guilt to shame,” says Joel Blackstock, clinical director at Taproot Therapy Collective in Birmingham, Alabama, where he specializes in complex trauma and frequently works with professionals dealing with the “shame spirals” that follow public or professional failures.

“In psychology, we distinguish these carefully,” he adds. “Guilt is the feeling that, ’I did something bad.’ It is a motivator for repair. Shame is the feeling that ‘I am bad.’ When a person tries to make amends but is met with continued distrust, their nervous system perceives this as ‘social exile.’”

He explains why this is such a frightening prospect and experience, whether it’s conscious or subconscious.

“For a social primate, exile is a survival threat,” Blackstock says.

“When we feel we will never be trusted again, the brain’s social engagement system — the ventral vagal complex — shuts down. We enter a state of functional freeze or depression. We stop trying to ‘do right’ because the feedback loop is broken.”

This can lead to different emotions and overwhelm.

“The desperation Junod describes is the nervous system screaming for re-integration into the tribe. Without a path to earn back trust, the psyche begins to collapse under the weight of its own perceived defectiveness.”

“When we believe we’ve violated a value, a standard or a role expectation, the emotional experience is often deeper than embarrassment, it can become shame and, in some cases, moral injury — ‘I have fractured what I believe I should be,’” says Tawanna-Marie Woolfolk, a trauma therapist, whose work centers around trauma, shame, moral injury and the nervous system, especially how humans repair after rupture, rebuild trust and return to relational safety with self and others.

“That inner verdict can create a heavy, depressive quality: rumination, self-doubt, reduced motivation and a sense of social threat,” she adds.

“The nervous system may interpret ‘I won’t be trusted again,’ as a form of relational danger because in many human contexts, trust equals belonging, livelihood and safety.”

The impact is significant and can become a regular re-examination of the error.

“Psychologically, this can produce a harsh internal prosecutor: the person repeatedly replays what happened, searches for evidence they’re unworthy and becomes hypervigilant to cues of rejection,” Woolfolk says.

When other people’s judgment is ongoing and intense, people may choose unhelpful reactions and responses.

“Interpersonally, if others are withholding trust, the person may oscillate between overexplaining and overperforming to earn it back or withdrawing to avoid further harm,” Woolfolk explains.

“Both patterns can keep them trapped in the very identity they’re trying to outgrow.”

There is a better mindset and approach.

“What helps is the difference between remorse and collapse,” Woolfolk teaches.

“Remorse is a signal of values and a desire for repair. Collapse is when shame convinces the person that repair is impossible and that their identity is permanently stained,” she says.

What Junod received from Rogers was life changing and helped him get unstuck.

“A trustworthy response from another person can interrupt that shame loop,” Woolfolk says, “especially if it recognizes the humanity of the person while still holding ethics and accountability intact.”

“I think that (Rogers) saw that I needed to be trusted again and he gave me that,” Junod told Stephanie Russell-Kraft in the Columbia Journalism Review.

“That was the great gift he gave me. He trusted me. And I think he trusted me because he saw the need in me.”

That is revealing.

“This is a perfect example of what Franz Alexander called a ‘Corrective Emotional Experience,’” Blackstock says. “Fred Rogers did not wait for Junod to prove he was trustworthy; he offered trust as an intervention.”

Rogers may or may not have understood what he was doing yet it was making a positive, healing difference. Blackstock explains more:

“From a clinical perspective, Rogers was operating with high ‘mentalization,’ the ability to see past behavior to the internal state of another. He saw that Junod’s cynicism or wariness was actually a defense mechanism protecting a deep wound of shame,” Blackstock details.

“By extending trust before it was technically ‘earned,’ Rogers bypassed Junod’s defenses. He signaled safety.”

An Important Lesson

“This tells us that Rogers understood the physics of redemption: you cannot shame someone into being better; you have to love them into it,” Blackstock says.

“By trusting Junod, he gave him a new identity to live up to. He interrupted Junod’s internal narrative of ‘I am a bad journalist’ and replaced it with ‘I am a person worthy of trust.’ That is a transformative psychological act.”

There is more that was taking place.

“From limited information, it suggests Rogers had a strong capacity for attunement: the ability to perceive another person’s emotional state and unmet need beneath the surface behavior,” Woolfolk says.

The “‘He saw the need in me (that Junod refers to),’ points to a relational moment where Junod’s internal experience — wary, self-questioning, possibly ashamed — was met with something steady and generous, rather than suspicion,” she adds.

This can prove to be a valuable offering and act.

“Psychologically, that kind of interaction can serve as a corrective emotional experience, not because it erases wrongdoing or standards, but because it offers an alternative narrative: ‘You are more than your worst moment. You can still be in relationship. You can still be trusted with a next chance,’” Woolfolk explains.

She goes deeper.

“In trauma terms, it’s a form of co-regulation,” where one person “provides enough steadiness that the (other) person can reorganize internally, regain dignity and return to ethical action without drowning in self-contempt,” Woolfolk says.

“To have people trust you and believe is a profound thing,” Junod discovered and said.

That is a strong expression.

It’s important to recognize his “readiness,” to be so affected, Woolfolk says.

“People who are defended, entitled or unremorseful, rarely experience trust as a ‘gift,’” she points out. “The fact that Junod experienced it as profound suggests he was in a receptive, humbled state: open to repair, rather than purely focused on image management.”

Blackstock also likes the use of “profound.”

He says it “is the correct word because trust is the foundation of sanity. We are not solitary creatures; we co-regulate each other.

“If no one believes us, we actually begin to lose our grip on reality, a phenomenon often seen in ‘gaslighting,’ but also in social isolation.”

Healthy Reality

“We need to be trusted to feel real. This goes back to Attachment Theory,” Blackstock says. “A child only knows they are safe and ‘good’ if the parent trusts them and reflects that trust back. As adults, when we lose the trust of our community, we lose our ‘secure base.’

“We spend all our energy scanning for threats rather than creating, working or loving. Being trusted allows the nervous system to settle. It frees up the energy that was being used for defense and allows it to be used for connection.

“It is the oxygen of the human spirit.”

Junod came to regret his approach and character after how he handled the feature on Spacey. The backlash shook him to his core and in a way, figuratively speaking, paralyzed him for a while. Rogers helped him regain emotional, psychological balance.

“Trust isn’t just a social preference,” Woolfolk says. “For many of us, it’s a core condition for nervous-system ease and for identity stability.

“Being trusted communicates: ‘You belong. You have standing here. You are safe enough to be known.’

“When trust is lost, it can threaten not only relationships but also livelihood, community and self-concept, especially in fields where credibility is central.”

It’s a critical, core component of our existence and relationship with others.

“The need is also developmental,” Woolfolk says.

“Across a lifespan, we organize around being seen accurately and held in ‘earned safety’ with others. When someone says they were ‘desperate to be trusted,’ that can reflect a deep longing to be restored to the moral community, to be regarded as capable of integrity again,” she explains.

“That’s why ‘profound’ fits: trust is tied to belonging, meaning and the felt sense that our future is still possible.

Subscribe for free (or paid, for additional benefits)

Follow on LinkedIn for more

Communication Intelligence began as online magazine (2021-2024) on another platform and during that time, also became a free-or-paid newsletter (2023 - present) on Substack. The C.I. brand additionally offers individuals and organizations a variety of services, from written communications as well as communication consulting and coaching.

The newsletter is written by a former newspaper reporter, magazine writer, talk show host and communications consultant and advisor.

This exploration of trust as a neccessity for nervous system regulation is brilliant. The distinction between guilt as 'I did something bad' versus shame as 'I am bad' feels especially relevent to cancel culture dynamics right now. Back when I was managing a small team, someone made a big mistake and I watched them spiral - turns out just creating space for them to still contribute (rather than freezing them out) made all the diference in their recovery.

I loved this one, Michael.

A junior developer on my team shipped code that crashed our production environment early Monday morning. Yikes! Everyone was furious. He was devastated, convinced his career was over. The next week, I assigned him the critical refactoring project everyone else wanted. People thought I was crazy. But I told him, 'You learned more from that mistake than anyone else here knows. I trust you with this.' Three years later, he's our best engineer. I didn't know I was offering a 'corrective emotional experience'. I just saw someone drowning in shame who needed to be trusted back into competence. I was in that same position so many times before.