1-on-1 Meetings Limit Team Learning

One entrepreneur says, for his organization, there is a better way. A behavioral and organizational psychologist - who is also a founder - agrees and disagrees.

One-on-one meetings are, in theory and likely in practice, valuable exchanges for leaders to communicate with their people and help them professionally and personally develop to benefit the organization — and ideally, the employee.

Not everyone believes it's the most helpful way.

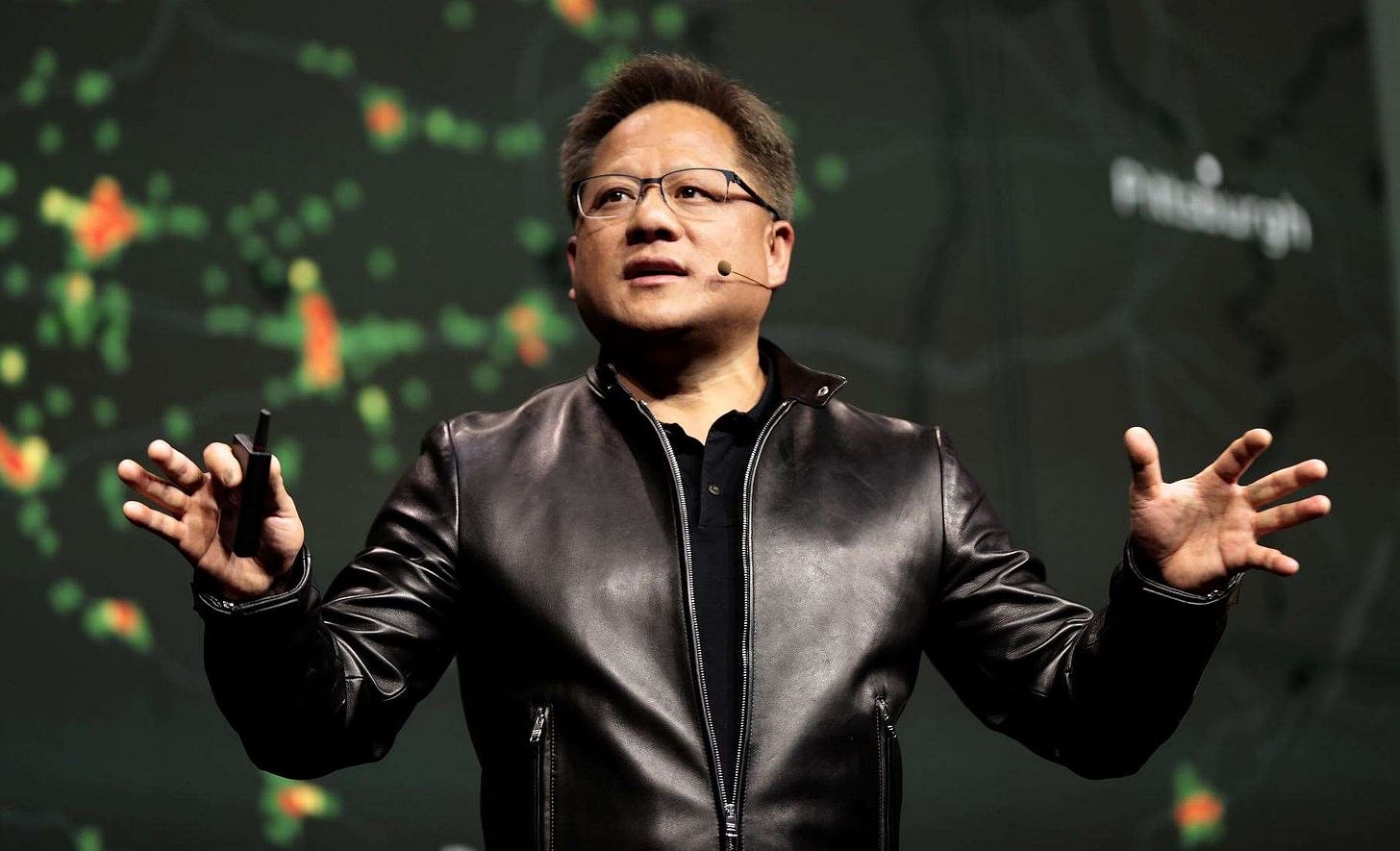

Jensen Huang, the CEO at NVIDIA, a multinational corporation and technology company that focuses on artificial intelligence computing, has 60 direct reports and yet, zero 1-on-1 meetings. He says that is by design.

"I'm certain that it's the best practice,” Huang recently said in an interview that was shared on LinkedIn.

He goes on to explain his reasoning.

"Feedback is learning. For what reason are you the only person who should learn this?” Huang said about communicating privately in 1-on-1 sessions.

“We should all learn from that opportunity. For me to reason through it in front of everybody helps everybody learn how to reason through it.”

The bottom line, he asserted is, there is much lost by the shortsighted, in his mind, norm of individual coaching.

"The problem I have with one on one's and taking feedback aside is you deprive a whole bunch of people that same learning,” Huang said. “Learning from mistakes, other people's mistakes, is the best way to learn."

That philosophy and leadership communication for employee feedback and learning has both positive and concerning components.

“Huang’s emphasis on shared learning is bold,” said Bob Hutchins, a behavioral and organizational psychologist and the founder and president at Human Voice Media, an on-demand CMO and AI advisory services company.

“By removing the walls of one-on-one meetings, he creates an environment where everyone can learn from each other’s mistakes and reasoning. It sends a message: mistakes are lessons and those lessons belong to the team, not just the individual.”

He adds that not all organizational leaders and team members will agree with Huang, maybe for good reasons and definitely, understandable ones.

“It’s a practice that might not work for everyone,” Hutchins says. “Public feedback can be helpful but it assumes that everyone is equally comfortable with open conversations, which isn’t always the case. Some might hesitate to share openly or feel discouraged in such settings.”

Huang may not recognize those points or worse, possible bigger holes in his beliefs.

“There’s a risk in relying too heavily on group learning,” Hutchins says. “Not every issue is suited for public discussion. People facing personal challenges or complex feedback might feel vulnerable in an open setting. One-on-one conversations provide the safety to dig into these nuances.”

There are other costs involved, Hutchins insists.

“Additionally, the absence of private feedback can mean missing out on moments to connect deeply with individuals, understand their unique aspirations or offer tailored guidance,” he says.

That may result in preventing or damaging the well-being of relationships and organizational strength. “Those moments often build trust and loyalty, which are harder to foster in group settings,” Hutchins offers as a reminder.

He does see value however in some of what Huang is a proponent of and practices.

“Huang’s approach reinforces the idea that feedback isn’t only about pointing out mistakes — it’s also about helping the entire team grow together,” Hutchins says.

“That’s powerful in my opinion (because) it shifts the culture from blame to shared responsibility.”

Hutchins recognizes something else of value that is often unusual.

“What resonates most is the transparency he encourages: letting others see how decisions are made and problems are worked through not only builds trust but also gives people tools to handle similar situations in the future,” he says.

“That kind of openness can inspire growth across the board.”